Re-Membering Korea: Buying and Selling Dreams

My personal practice of decolonization is reclaiming and re-membering my Korean ancestry that has been fractured, warped, and omitted from my consciousness through the accumulated trauma of colonization, war, imperialism, and diaspora. Korean peoples call this ‘han,’ the inheritance of ancestral rage and grief. When I first learned about 한 (han), I could feel it in my body; I knew exactly what it was.

Dreamwork has been an essential part of my decolonization journeying. My life feels more nourished and expansive, reviving ancestral roots and feeding my insatiable curiosity about where I come from…

On this particular day, my curiosity led me to Bongsu Park’s digital-portal, Dream Auction, detailing a Korean tradition of buying and selling dreams. This London-based Korean sibling of the diaspora has chronicled historical accounts of dreams that were sold, dating all the way back to Silla Dynasty (57 BCE - 935 CE).

One particular account is the story of two sisters, Munhui and Bohui. Bohui dreamt of climbing a mountain and covering the entire capital of Silla with her urine. Munhui was drawn to the dream and bought the dream from Bohui in exchange for a silk skirt. Later, Munhui married Chunchu, who became the King Muyeol of Silla, known for uniting the three kingdoms of Korea. Together, they birthed six sons who also became kings. Bohui’s dream of flooding the capital was manifested in Munhui and King Muyeol’s expansive rule of Korea, even through their children.

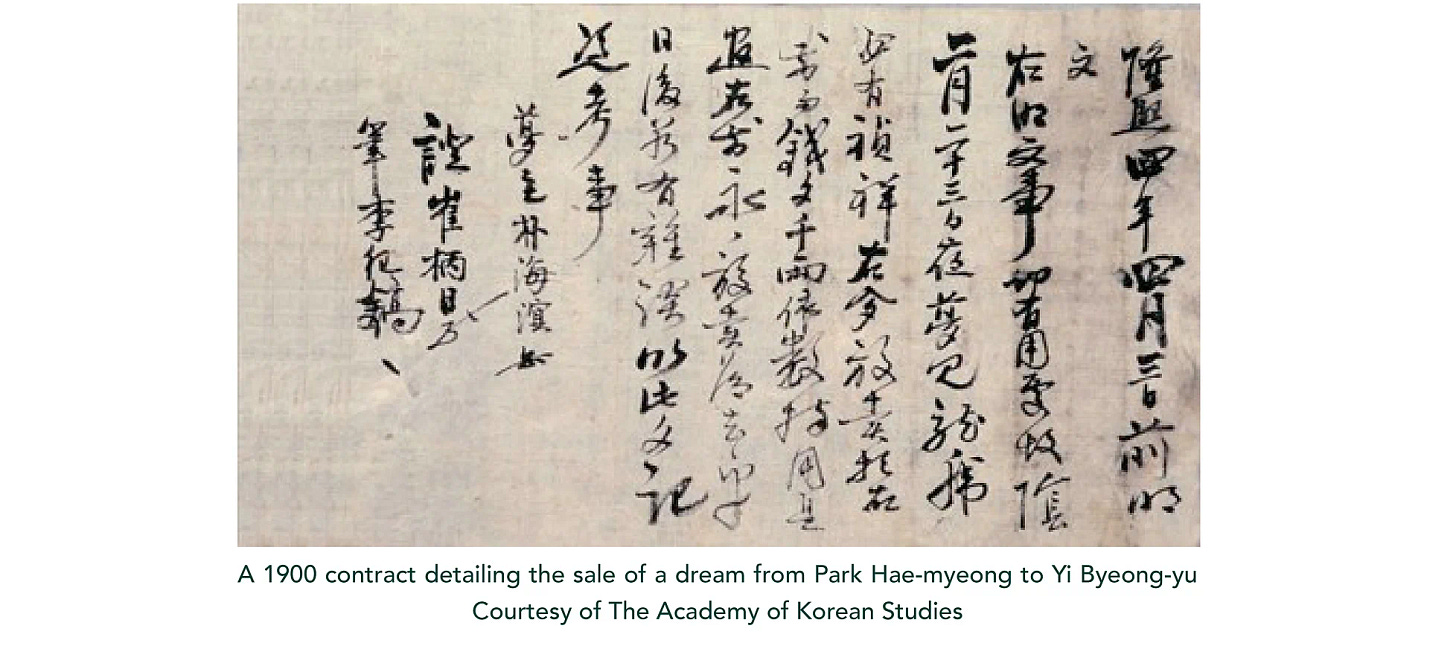

In her extensive research on dream transactions, Park even came across a contract from Chosun Dynasty that details the sale of a dream. You can read the details of these historical accounts of dream transactions here.

I called my mother to confirm this tradition. I could hear the nostalgia in her voice as she described the seemingly playful remarks of telling someone they’d like to buy their auspicious dream! She even shared that if a dream felt ominous, it was common practice to keep the dream to one’s self for a little while before telling anyone about it, lest they speak it into existence.

In an interview with The Museum of Dreams, Park describes how she first participated in this tradition when she was telling her Korean friend about dreaming of eating a blueberry the size of a tomato. Her friend responded that she needed to buy her dream. When Park inquired why, her friend shared that she was trying to get pregnant and the Korean interpretation of dreaming of eating fruit is traditionally a sign of birthing a daughter. So, in exchange for a dream, her friend paid for the cake and coffee they enjoyed together that day. Two months later, her friend called to tell her she was pregnant! For more fun and surprising details of this encounter, do take time to read her interview.

The allure one feels toward another’s dream seems to signal an intuition, knowing that the dream is meant for the listener more than it was meant for the dreamer. In my privileged position as a Third Culture Kid practicing co-liberatory ways of being, I’m honestly not too keen on the idea of the transactional design of this practice. I much prefer the act of gifting the dream through sharing and resonance, as I described in my previous post, Dreams meant for others. I appreciate this point of tension as an opportunity to alchemize this piece of my ancestral roots with where I am today into something that honors both while transmuting them into a life-affirming practice, or at least the seeding of it.

Park has already seeded and blossomed her own version of alchemy in her Dream Auction events. This Dream Auction Catalog features dreams, submitted by people through dreamauction.org. The dreams were beautifully displayed on custom-designed hanging scrolls and auctioned to the highest bidder. A portion of the funds were donated to local nonprofit organizations in Korea or London, where the events were held.

[Image from dreamauction.org]

As I continue to re-member Korea into my consciousness, I also nurture this sacred process with practices like dreamwork done through a han-releasing, decolonial and co-liberatory lens (don’t be like Descartes and his posse!).

I thank my ancestors for their wise, indigenous ways.

I thank my ancestors for guiding me to them.

I thank my ancestors for sowing the path towards more generous and generative ways of humaning for the greater good of the collective.